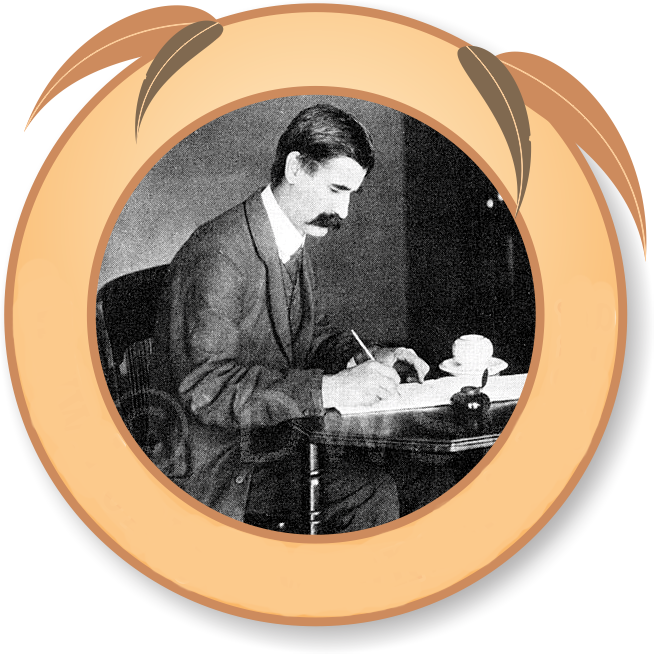

Much has been speculated, and written, about Hannah Thornburn – the young woman with whom Henry Lawson was reputed to be infactuated. I’d heard the story before, but what did I actually know of Hannah Thornburn; who was she, and how, when and why did she feature in Henry’s life?

Hannah Forrester Thornburn was born ~ 1877, the daughter and only child of Betty Forrester and John Thornburn. Around 1893, at the age of 16, Hannah’s family moved from Melbourne to 62 Church Street Balmain, NSW. Her father was a commercial traveller and later a bookseller in Balmain. He was believed to be a weak minded man who drank, and was often out of work, so Hannah was the breadwinner, working as a book keeper and clerk with Ford’s Memorial Engraving Company, Printers, King St, Sydney.1

In 1889 the family moved back to Melbourne and then returned to Balmain again in 1896. Hannah worked as a part-time model for sculptor Nelson Illingworth, a friend of Henry. At the time Henry and Hannah met (1897), he was thirty and an established author and poet and she was twenty. Both Hannah and her friend Winifred Holford had become members of the YWCA and taught Sunday School at a Congregational Church. According to Winifred, Hannah was a tender minded person with a ready sense of humour and affectionate nature. Winifred also claimed that Hannah was of small stature, with a fair complexion, grey eyed with reddish gold hair and was inclined to be the ‘clinging vine type’. She was slender and attractive but not handsome.1

Henry describes Hannah in verse 3 of his poem Hannah Thornburn (1905):

Her hair was red gold on head Grecian,

But fluffed from the parting away

And her eyes were the warm grey Venetian

That comes with the dawn of the day.

No Fashion nor Fad could entrap her,

And a simple print work dress wore she,

But her long limbs were formed for the ‘wrapper’

And her fair arms were meant to be free.

The finer details of Henry’s relationship with Hannah remain open to conjecture. However there seems no doubt there was infatuation on both sides. According to Henry’s friend Bertram Stevens (former Premier of NSW), Henry is said to have turned to Hannah, a young woman who worshipped him, at a time when his wife Bertha was finding it difficult to cope with his increasingly irresponsible behaviour. Hannah, it seems, supplied the flattery and encouragement that Bertha is said to have withheld. The fact that Henry knew Hannah well in 1899 is confirmed by Henry’s inscriptions to her in copies of While the Billy Boils and In The Days When the World Was Wide. Author and historian Colin Roderick suggests that there is enough circumstantial evidence to reinforce the conviction that there was a love affair, substantiated by some of the lines from verse 2 of Hannah Thornburn2 :

There was never a church that could marry,

For never a court could divorce

In the season of Hannah and Harry

When the love of my life ran its course.

Hannah died in a Melbourne hospital on 1 June 1902, aged 25, ‘of an injury she inflicted on herself’3. She was buried at Melbourne’s Boroondara Cemetery (Kew), in a ‘general’ (pauper) grave belonging to the Young Women’s Christian Association who paid the 3 pound cost of her funeral. In attendance were a representative of the YWCA, a clergyman, gravedigger and undertaker. Henry was in London when Hannah died, and arrived back in Australia on 12 July 1902 on board the steamer ‘Karlsruhe’ which docked in Adelaide. He is believed to have been deeply affected by her death, so much so that he would write several poems to her: To Hannah (1904); Hannah Thornburn (1905), The Lily of St Leonards (1907) and Do They Think I Do Not Know (1910). Henry was mistaken when he penned the words ‘She was buried at Brighton, where Gordon sleeps’ – a line from Do They Think I Do Not Know – as her grave has always been at Kew.

In 1971, the Henry Lawson Society met the cost of placing a bronze plaque and a concrete slab and headstone on Hannah’s grave. On 5th February 1972, Dr Colin Roderick, Life Honorary Member of the Society, unveiled the plaque. The Lawsonian (March, 1972 edition) states : ‘the function attracted considerable interest in both press and literary circles. In spite of a very hot afternoon the attendance was good. At the last minute we had to re-adjust our programme to include the well known folk singer, Shirley Jacobs, who found it possible, owing to our change of date, to assist with Lawson songs from her recent recording’.4

I had learned much from delving into the story of Hannah Thornburn. I decided to visit her grave and read Henry’s Hannah Thornburn to her. The Melbourne day was cold and overcast, the cemetery was quiet, and I imagined Hannah was listening. To me, Hannah remains somewhat of an enigma, a feeling reinforced as I silently left her in peace.

Leigh Hay (Lawsonian Editor)

1Information written by H Smith (The Lawsonian, July 2006), submitted by Brenda Carew.

2McLellan, Gwenyth Dorothy, Henry Lawson’s women: the angel/devil dichotomy, Master of Arts (Hons.) thesis, Department of English, University of Wollongong, 1991. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2195.

3’In Black and White’ The Herald, Monday Jan 24 1972.

4 Information submitted by Elizabeth Wright (The Lawsonian, March 1972).